PRE2020 4 Group1

Project Title t.b.d.

<div#bodyContent sup {

font-size: smaller; vertical-align: baseline; position: relative; bottom: 0.33em;

}

- bodyContent sub {

font-size: smaller; vertical-align: baseline; position: relative; bottom: -0.25em;;

}>

Team members

| Members | Student ID | Faculty | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kashan Alidjan | 1224924 | Electrical Engineering | k.m.s.alidjan@student.tue.nl |

| Sijt Hooghwinkel | 1228761 | Automotive | s.j.c.hooghwinkel@student.tue.nl |

| Damaris Jongbloed | 1241057 | Computer Science | d.a.jongbloed@student.tue.nl |

| Emma van Oppen | 0963999 | Computer Science | e.y.v.oppen@student.tue.nl |

| Laura Verbeek | 1428063 | Biomedical Engineering | l.h.e.verbeek@student.tue.nl |

Introduction

In 2020 the Dutch government spent 8.9 billion euros on roads, railways and waterways.[1] In the Netherlands, there are 125,575 kilometres of roads, which amounts to 27000 euros per km. People new to the Netherlands often claim how well-maintained our roads are, and the Netherlands ranks second in road quality worldwide.[2] Road quality is valued highly in the Netherlands due to a large number of cyclists. Minor damage will not be noticeable in a large car, but small cracks can lead to dangerous situations on a bicycle. [3] To keep the roads in such great condition, a lot or work is done. Municipalities, provinces and the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management work round the clock to repair damage, but they all use a different system. Most damage is detected by periodic checks, road workers and civilian complaints. To improve the efficiency and cost of these detections, this project intends to present a solution that passively detects damage and stores this in a central database, to be inspected by the responsible parties.

In order to investigate the need of such a device, a survey was sent out to municipalities, asking them if they see a need for such a detection device. 30 out of 49 replies indicated that a global detection system could be an improvement, and more in depth feedback was provided. For example, most municipalities use the CROW mechanism to decide priority of repair. The municipality Bladel says: "A guideline has been developed for road management that serves as a tool to arrive at the most optimal long-term planning: that is the actual translation of the quality level into concrete maintenance measures. This road management system is laid down in publications 146 and 147 of the CROW. This is the most important standard work for road management in the Netherlands. This system is used by most municipalities, provinces and water boards and is often seen as a guideline in case law."

Furthermore, civilian complaints were done in different interfaces, such as BuitenBeterApp, Fixi or the Meld & Herstel app. Reimerswaal said: "FIXI reports from residents are immediately passed on as an order for repair to a number of house contractors who work for us on a contract. This if the report is serious enough, which may be apparent from the enclosed photo or recording by our on-site supervisor." Ijsstelstein added: "A national reporting system that all municipalities can use is an improvement. There are so many now, this causes too much noise on the reports from the public space, this delays and causes dissatisfaction for the residents." The main concerns indicated in the survey were that different municipalities have different budgets for repair (as indicated by Kampen and Ijsselstein), there could be too many or too few detections (due to inaccuracies) and all damages require manual inspection anyway.

Objectives

Following the survey, requirements were gathered to lead this project to success.

- The product needs to save money. Without this, there is no interest from municipalities, to whom the product is aimed. If the product is sufficiently cheap, real-world implementation is easier.

- The damage needs to be reported to the right road authority. The current system for road repair is individual, and it was indicated this is an important feature to assign repair.

- Furthermore, accurate location data of the damage should be reported.

- Only damages should be reported, for example, speedbumps should be ignored. However, if the damage is not severe enough, and does not need to be repaired, it should not be reported either.

- The CROW framework should be supported. Since most municipalities use this framework, it makes sense to provide an implementation in the database.

- Accordingly, priorities can be assigned to reports.

- Some damages will only be noticed with the eye, so these should be reported manually.

- Additionally, the product will provide more profit when implemented on a large scale. Therefore, it should be easy to implement and use.

Dit deel mist nog motivatie: The main objective of this project is to develop a device that measures road surface quality by detecting irregularities in the pavement, such as potholes and cracks, that are encountered while driving around. This device can be placed onto a vehicle and will collect data on these irregularities using several different sensors, such as an accelerometer and a GPS module.

Through the use of crowdsourcing, the collected data, along with GPS locations, can be used to visualize the locations of potholes, cracks and other damage to the road’s surface, thus creating a mapping of the overall road quality. This data can be used to quickly assess where the damage is the most severe and which roads are in need of repair. As such, road maintenance can be planned more immediately when problem areas are detected, which can contribute to an increase in road safety.

- Collect data on potential locations of potholes, cracks and other road surface damage.

- Visualize the locations of detected road damage by overlaying the collected data on a map.

- Enable quick assessment of where the damage is most severe and repair is necessary.

- The device must be cost effective to enable widespread usage.

USE analysis

Users

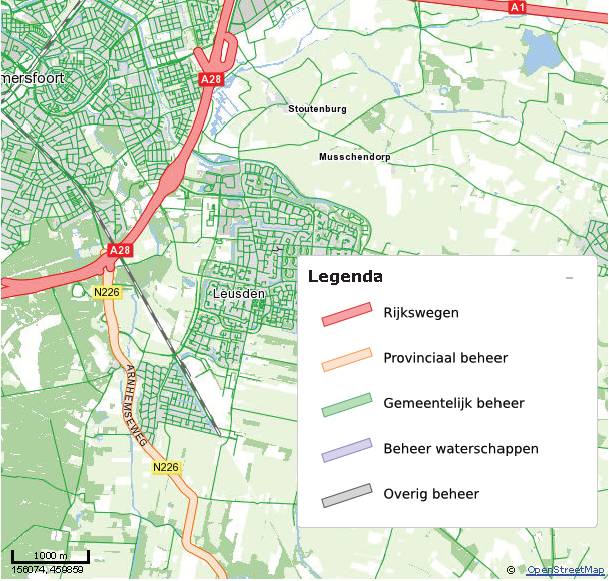

The public roads in The Netherlands are not maintained by one organization. The management is mainly shared between Rijkswaterstaat (highways), provinces and local municipalities. The two latter are responsible for the “N” roads, non-highway roads.

People that have the device installed on their vehicle can be considered as passive users as they do not have to interact directly with the device if they wish. They will need to monitor the physical state of the device and have the device replaced/repaired if needed. The users can also actively interact with the App to see their contribution and edit wrongful detections of the system (false positives) or add locations where the system has not detected anything (false negatives).

Society

Societal stakeholders are all road users.

Enterprise

If a road repair needs to be done a contractor will be used to perform this repair.

Depending on the means of installation and technical knowledge that is required to perform installation (TBD!), this may need to be done by a garage. Several garages could be selected to have an inventory of the devices to install on customers cars during their general inspection (APK) or with a service.

Car insurance companies are also stakeholders in this project. Car owners could make use of their insurance policy to claim for damages on their vehicle because of bad roads. Better quality roads would mean insurance companies would have to compensate fewer people.

State of the art / Research

TODO

The links to all the State of the art research are shown in the appendix

Plan

Approach & Milestones

To meet our goals, we subdivided our research into 12 milestones. For each milestone, a short description is given to clarify what needs to be done to reach the milestone.

- Find a subject: to do the project, we need to determine the subject that we will focus on. For this, we should think about what type of research we want to conduct (e.g. literature analysis, experimenting, designing, building a prototype…). Other things to keep in mind are:

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the group?

- Which projects are possible to do within 8 weeks?

- Literature study: the second milestone is to gain knowledge about the possibilities already used for our problem. In this literature study, we will look at the State-of-the-Art, and what the pros and cons are of these solutions to the problem. This knowledge can be applied to improve our own research.

- Survey: to find out about the needs of the users, we will do a survey. It will help us define the problem.

- Conceptual design: in the fourth step, we make multiple designs for the problem. For each design we will look at the pros and cons to find the best design. We can choose the best design or combine the strengths of multiple designs to form a new concept.

- Functional description: once we know what the concept will look like, we need to figure out which components are needed to build the main parts of the design, and we have to look up which components/materials are available in the store or online. For example: how is the product supplied with power? A battery? A cable? Furthermore, we should start working on the software.

- Final design concept: using the knowledge about the materials found in (5), functional description, we should revise the conceptual design and make some adjustments if needed. The conceptual design will be refined to make the final design concept.

- Detailing: the next step is detailing, which means that we should look at the specifications of all the components. Using the same example as in (5), functional description, which battery is sufficient to keep the product working for an X amount of time. In this step it is also important to look at the dimensions of all the components to fit them all in the casing.

- Mock-up: making a mock-up of the concept using cheap materials and/or a CAD design.

- Software: once the functional description is made, a start should be made on the software. The software should be finished before the realization (10).

- Realization: once we are satisfied with the prototype, we should order the components and start building the concept (make a BOM). First all components should be tested independently before putting the concept together. Hardware and software are combined.

- Testing: the prototype should be tested. (Minor) adjustments can be made in the software and/or hardware to refine the product.

- Results and evaluation: evaluation of the results of the test will give insight in the quality of the product. Possible areas of improvements are mentioned in the evaluation, as well as the strengths of the design.

- Final presentation and discussion: finalize the wiki page and prepare for the final presentation.

Deliverables

The deliverables for this project consist of the following items:

- The physical prototype

- An app that collects the data output of the product

- A demonstration of the product, shown during the video presentation

- The wiki page containing main topics, such as:

- Problem statement

- USE aspects

- Product

- Planning

- A video presentation regarding the product, process and most important findings.

Planning

| Week | Milestone | Milestone name | Task | Responsible | Deadline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Find a subject | Brainstorm | All | 25-4 |

| 2 | Literature study | All | 25-4 | ||

| 2 | 2 | Literature study | Finish literature | Emma, Laura | 29-4 |

| 3 | Conceptual design | Sketch app | Emma, Sijt | 2-5 | |

| 3 | Conceptual design | Sketch physical design | Kashan, Laura | 2-5 | |

| 3 | Conceptual design | High level interaction (USE diagram) | Damaris | 2-5 | |

| 1 | Find a subject | Problem definition rewrite | Emma, Laura | 2-5 | |

| 1 | Find a subject | Problem definition research | All | 2-5 | |

| 3 | 4 | Functional description | All (tbd) | 6-5 | |

| 5 | Final design concept | All (tbd) | 9-5 | ||

| 4 | 6 | Detailing | All (tbd) | 13-5 | |

| 8 | Software | Emma, Sijt | 16-5 | ||

| Order parts | Tbd | 16-5 | |||

| 5 | 7 | Mock-up | Kashan, Laura, Damaris | 23-5 | |

| 8 | Software | Emma, Sijt | 23-5 | ||

| 10 | Testing | Testplan, perform tests | All | 23-5 | |

| 6 | 9 | Realization | Perfect product | Kashan, Laura, Damaris | 30-5 |

| 7 | 11 | Results and evaluation | All | 6-6 | |

| 12 | Presentation and discussion | All | 6-6 | ||

| 8 | Overtime | All | 13-6 |

Product Research

State of the Art

Sensors

Smartphone

Logbook

Week 1

| Name | Student ID | Time spent | Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kashan Alidjan | 1224924 | 7.5h | Intro (1h), Meeting (3h), Research (1.5h), Reading old projects (1h), Deliverables (0.5h), SoTA (0.5h) |

| Sijt Hooghwinkel | 1228761 | 7h | Intro (1h), Meeting (3h), Reading old projects (1h), Users (2h) |

| Damaris Jongbloed | 1241057 | 7.5h | Intro (1h), Meeting (3h), Research (1.5h), Problem statement (2h) |

| Emma van Oppen | 0963999 | 8.5h | Intro (1h), Meeting (3h), Research (3h), Objectives(1h), Wiki(0.5h) |

| Laura Verbeek | 1428063 | 9h | Intro (1h), Meeting (3h), Approach+milestones (2.5h), SotA (2.5h) |

Week 2

| Name | Student ID | Time spent | Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kashan Alidjan | 1224924 | 9h | Meeting (3h), Design (1.5h), SotA summaries (2h), preparation (2h), wiki (0.5h) |

| Sijt Hooghwinkel | 1228761 | 8h | Meeting (3h), Android studio (1h), researching OSM (1h), SotA summaries(3h) |

| Damaris Jongbloed | 1241057 | 7h | Meeting 27-4 (1h), Meeting 29-4 (2h), Proofreading (0.5h), SotA (3h), Update planning (0.5h) |

| Emma van Oppen | 0963999 | 14h | Meeting (3h), Research/SotA (9.5h), Wiki (0.5h), App Setup (1h) |

| Laura Verbeek | 1428063 | 10.5h | Meeting (3h), reading the work of others (0.5h), SotA (5.5h), Design (1.5h) |

Week 3

| Name | Student ID | Time spent | Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kashan Alidjan | 1224924 | ||

| Sijt Hooghwinkel | 1228761 | ||

| Damaris Jongbloed | 1241057 | ||

| Emma van Oppen | 0963999 | ||

| Laura Verbeek | 1428063 |

Week 4

| Name | Student ID | Time spent | Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kashan Alidjan | 1224924 | ||

| Sijt Hooghwinkel | 1228761 | ||

| Damaris Jongbloed | 1241057 | ||

| Emma van Oppen | 0963999 | ||

| Laura Verbeek | 1428063 |

Week 5

| Name | Student ID | Time spent | Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kashan Alidjan | 1224924 | ||

| Sijt Hooghwinkel | 1228761 | ||

| Damaris Jongbloed | 1241057 | ||

| Emma van Oppen | 0963999 | ||

| Laura Verbeek | 1428063 |

Week 6

| Name | Student ID | Time spent | Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kashan Alidjan | 1224924 | ||

| Sijt Hooghwinkel | 1228761 | ||

| Damaris Jongbloed | 1241057 | ||

| Emma van Oppen | 0963999 | ||

| Laura Verbeek | 1428063 |

Week 7

| Name | Student ID | Time spent | Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kashan Alidjan | 1224924 | ||

| Sijt Hooghwinkel | 1228761 | ||

| Damaris Jongbloed | 1241057 | ||

| Emma van Oppen | 0963999 | ||

| Laura Verbeek | 1428063 |

Week 8

| Name | Student ID | Time spent | Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kashan Alidjan | 1224924 | ||

| Sijt Hooghwinkel | 1228761 | ||

| Damaris Jongbloed | 1241057 | ||

| Emma van Oppen | 0963999 | ||

| Laura Verbeek | 1428063 |

Appendix

Municipal Questionnaire

The table below shows the results of the questionnaire sent out to several municipals in The Netherlands. The questions that was asked was: "Does the municipality see added benefit to using a global and continuous detection system for road quality?". In total 52 municipals reacted to the questionnaire.

| Answer | Amount | General Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | 19 | Doing more measurements is beneficial. Road user would not have to figure out how to contact municipal to report damages. A method used by every municipal would be positive. |

| Negative | 18 | Current system works properly. A sufficiently covering system is a utopia. Up until now there is no national system that benefits the municipals |

| Undecided | 15 | Would result in more alerts. Municipal would still have to check the damage but could save time. Only when saving money. Should support the CROW standards. |

A large amount of municipals reacted either negatively or undecided. This is most likely because the question that was asked is very broad in terms of technical implementation. In most cases the contact person could not imagine how such a system would be implemented, hence being undecided.

Links of the State of the Art research: [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28]

References

- ↑ Dutch Government. (2019). Summary of the 2020 Budget Memorandum.

- ↑ Schwab, K. (2019). The Global Competitiveness Report 2019.

- ↑ Wagenbuur, M (2014). How come there are no potholes in the Netherlands?.

- ↑ Zang, Kaiyue & Shen, Jie & Huang, Haosheng & Wan, Mi & Shi, Jiafeng. (2018). Assessing and Mapping of Road Surface Roughness based on GPS and Accelerometer Sensors on Bicycle-Mounted Smartphones. Sensors. 18. 914. 10.3390/s18030914.

- ↑ Nunes, Davidson & Mota, Vinícius. (2019). A participatory sensing framework to classify road surface quality. Journal of Internet Services and Applications. 10. 10.1186/s13174-019-0111-1.

- ↑ Anaissi, A., Khoa, N.L.D., Rakotoarivelo, T. et al. Smart pothole detection system using vehicle-mounted sensors and machine learning. J Civil Struct Health Monit 9, 91–102 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13349-019-00323-0

- ↑ Y. -A. Daraghmi, T. -H. Wu and Ts!-Uí, "Crowdsourcing-Based Road Surface Evaluation and Indexing," in IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, doi: 10.1109/TITS.2020.3041681.

- ↑ Lushnikov, Nikolay & Lushnikov, Petr. (2017). Methods of Assessment of Accuracy of Road Surface Roughness Measurement with Profilometer. Transportation Research Procedia. 20. 425-429. 10.1016/j.trpro.2017.01.069.

- ↑ Smith, Kurt D., Ram, Prashant. (2016). Measuring and Specifying Pavement Smoothness.

- ↑ El-hariri, Esraa & Hassanien, Aboul Ella & Mohamed, Adham & Fouad, Mohamed & El-Bendary, Nashwa & Zawbaa, Hossam & Tahoun, Mohamed. (2014). RoadMonitor: An Intelligent Road Surface Condition Monitoring System. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. 323. 10.1007/978-3-319-11310-4_33.

- ↑ A. Tedeschi, F. Benedetto, A real-time automatic pavement crack and pothole recognition system for mobile Android-based devices, Advanced Engineering Informatics, Volume 32, 2017, Pages 11-25, ISSN 1474-0346, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2016.12.004.

- ↑ Ragnoli, Antonella & Blasiis, Maria & Di Benedetto, Alessandro. (2018). Pavement Distress Detection Methods: A Review. 10.20944/preprints201809.0567.v1.

- ↑ Tsai, Jung-Fa, Wang, Hsiu-Wen, Chen, Chi-Hua, Cheng, Ding-Yuan, Lin, Chun-Hao, Lo, Chi-Chun. (2015). A Real-Time Pothole Detection Approach for Intelligent Transportation System. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/869627.

- ↑ Abulizi, Nueraihemaitijiang & Kawamura, Akira & Tomiyama, Kazuya & Fujita, Shun. (2016). Measuring and evaluating of road roughness conditions with a compact road profiler and ArcGIS. Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering (English Edition). 3. 10.1016/j.jtte.2016.09.004.

- ↑ Nguyen, T., Lechner, B. & Wong, Y.D. Response-based methods to measure road surface irregularity: a state-of-the-art review. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 11, 43 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12544-019-0380-6.

- ↑ Astarita, Vittorio & Vaiana, Rosolino & Caruso, Maria Vittoria & Iuele, Teresa & Giofré, Vincenzo & F., De. (2014). Automated Sensing System for Monitoring of Road Surface Quality by Mobile Devices. PROCEDIA: SOCIAL & BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES. 111. 242-251. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.057.

- ↑ Astarita, Vittorio & Caruso, Maria Vittoria & Danieli, Guido & Festa, D.C. & Giofré, Vincenzo & Iuele, Teresa & Vaiana, Rosolino. (2012). A Mobile Application for Road Surface Quality Control: UNIquALroad. PROCEDIA: SOCIAL & BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES. 54. 1135-1144. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.828.

- ↑ Du, Yuchuan & Liu, Chenglong & Wu, Difei & Jiang, Shengchuan. (2014). Measurement of International Roughness Index by Using Z -Axis Accelerometers and GPS. Mathematical Problems in Engineering. 2014. 1-10. 10.1155/2014/928980.

- ↑ Seraj, Fatjon & van der Zwaag, Berend Jan & Dilo, Arta & Luarasi, Tamara & Havinga, Paul. (2016). RoADS: A Road Pavement Monitoring System for Anomaly Detection Using Smart Phones. 128–146. 10.1007/978-3-319-29009-6_7.

- ↑ Sharma, Sunil Kumar, Sharma, Rakesh Chandmal, Kumar, Mukul. (2019). Pothole Detection and Warning System for Indian Roads. 10.1007/978-981-13-6577-5_48

- ↑ Sattar, Shahram & Li, Songnian & Chapman, Michael. (2018). Road Surface Monitoring Using Smartphone Sensors:A Review. Sensors. 18. 3845. 10.3390/s18113845.

- ↑ F. Kortmann et al., "Creating Value from in-Vehicle Data: Detecting Road Surfaces and Road Hazards," 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), 2020, pp. 1-6, doi: 10.1109/ITSC45102.2020.9294684.

- ↑ Alessandroni, Giacomo & Klopfenstein, Lorenz & Delpriori, Saverio & Dromedari, M & Luchetti, Gioele & Paolini, Brendan & Seraghiti, Andrea & Lattanzi, Emanuele & Freschi, V & Carini, Alberto & Bogliolo, Alessandro. (2014). SmartRoadSense: Collaborative Road Surface Condition Monitoring. 10.13140/RG.2.1.3124.2726.

- ↑ Chatterjee, Sromona & Brendel, Alfred & Lichtenberg, Sascha. (2018). Smart Infrastructure Monitoring: Development of a Decision Support System for Vision-Based Road Crack Detection.

- ↑ Maeda, Hiroya & Sekimoto, Yoshihide & Seto, Toshikazu & Kashiyama, Takehiro & Omata, Hiroshi. (2018). Road Damage Detection Using Deep Neural Networks with Images Captured Through a Smartphone. Arxiv.

- ↑ Mertz, Christoph. (2011). CONTINUOUS ROAD DAMAGE DETECTION USING REGULAR SERVICE VEHICLES.

- ↑ Shouvik, Mani & Bhatt, Umang & Xi, Edgar. (2017). Intelligent Pothole Detection.

- ↑ Liu, Baolin. Using Object Detection to Find Potholes.