PRE2019 3 Group7

Group Members

| Name | Study | Student ID |

|---|---|---|

| Daan Schalk | 0962457 | |

| Job Willems | 1003011 | |

| Jasper Dellaert | 1252454 | |

| Sanne van Wijk | 1018078 | |

| Wietske Blijjenberg | 1025111 |

Subject

In the UK, the late night culture of “clubbing” is very popular with around 40% of the key target group being students.

Use a simulation to optimize the revenue of a bar or club.

When looking at Stratumseind these days, clubs and bars that were once flourishing look empty and silent. For a manager of such a bar, it may be difficult to decide what to improve to regain the glory of those golden days. Humans are complex, so their happiness and willingness to spend may depend on different factors combined in a specific way. Because of all these different factors, experimenting with them in real life is impossible work. On top of that, change in revenue might not be seen in a week, to be sure a longer observation period is needed. However, if you need to test a lot of different factors in a lot of different combinations, this takes ages.

That is where a simulation of the behaviours of the people in a bar or club might help. The simulation will make it easy to experiment with different factors, and adds the possibility to run multiple simulation in sequence. This way, certainty can be reached about the influence of a certain factor on the revenue, and managers of clubs and bars can come to decisions about what to improve to make their bar great again. The average club derives around two-thirds of tis revenue from the sale of beverages, and it is therefore a vital source of profits [1]. Therefore the simulation will be focusing on how to maximize the selling of beverages.

Objectives

- Main goal: assist the owner of a bar or dance hall with ideas on how to improve customer revenue.

- Construct an AI multi-agent simulation with which we can find what variables with what capacities are needed to maximize generated income.

- Analyse the reliability of such a simulation by discussing the observations of the client and the results of previous research done in this field (if any apply).

- Analyse the possibilities and shortcomings of such a simulation.

Research variables

Note: during the early phases of this project, variables are subject to change and may still be included/excluded.

General variables

Income

- Description: The amount of money spent by patrons inside the establishment during the evening/night in order to buy alcohol. Alcohol is the only product available, which has to be bought using euros as currency. At the start of the simulation, this variable will start at a value of 0 euros.

- Used in simulation: yes

- Reasoning: Income is a crucial variable, as the problem statement is based around creating as much income for the establishment as possible. All other variables used during the simulation do relate to the generated income to some extent.

Crowded level

- Description: Is the establishment filled with patrons or are there barely any people? An upper limit of the amount of people that can comfortably fit inside the bar/dance hall has been estimated (using room size and patron experience). The crowded level is defined as the ratio between the current amount of patrons and the upper limit, displayed as a percentage. At the start of the simulation, this variable will start at a value of 0 percent.

- Used in simulation: yes

- Reasoning: As the patrons' happiness can decrease significantly when the bar is overcrowded, it is important to weigh in this factor when evaluating the latter. Patrons can also become less happy when there are barely any other people inside.

Dancing crowd

- Description: Patrons can start and stop dancing at any time inside the establishment. The Dancing crowd is the amount of patrons that are currently dancing according to their patron state. At the start of the simulation, this variable will start at a value of 0.

- Used in simulation: yes

- Reasoning: This variable does not relate heavily to other variables. It is however used when a patron has to decide whether it will start or stop dancing. Because the ability for patrons to dance is an important element of the simulation, the dancing crowd is included.

Environment specific variables

Room size

- Description: The surface size of the singular room in which all patrons can be found inside the establishment. This room can be used for all patron activities, and is also the location in which alcohol is sold. The specific geometry of the room is neglected. The surface area size is given in cubic meters.

- Used in simulation: no

- Reasoning: While the size of the room plays a role when analysing an average day at a bar, it is often not the actual size that counts, but the percentage of the establishment that is filled with patrons. For this reason, the room size is accommodated inside the crowded level variable.

Amount of bathrooms

- Description: A bar or dance hall one or multiple toilets for both male and female patrons. While this is not obligated by the Dutch law to do so (for smaller establishments), an average bar or dance hall will have multiple toilets. This variable does not discriminate between toilets catered to women or men.

- Used in simulation: no

- Reasoning: It is determined [SOURCE?] that the amount of bathroom breaks or the amount of toilets does neither directly nor indirectly change alcohol sales. When a bar or dance hall does not have any toilets, then that might cause customers to not return to that establishment on subsequent nights. Because this research only analyses a singular regular day, it does not affect the simulation results.

In this [2] study it is shown that although people consume less alcohol during bahtroom breaks, bathroom breaks are so short that the "lost time" is easily compensated after the break, thus the total effect of bathroom breaks on alcohol consumption is zero.

Music

- Description: A bar or dance hall can play music throughout the day. It is assumed that the music genre that is played is appreciated by the patrons. The volume of the music can change, which can alter the behaviour of the patrons. The music can also be absent. This variable describes the volume of the music, which will start at a value of 0 dB.

- Used in simulation: yes

- Reasoning: Music volume can greatly change the behaviour of patrons [3][4][5][6]. While the genre of the music being played could also alter this behaviour, the exact relation could not be grounded by previously done research, and is thus omitted from the simulation.

=> It could though. Studies found that when playing drinking songs in a bar, the duration of stay and spending are both increased [7] [8].

Amount of active employees

- Description: The amount of people currently working in the establishment. While an employee can have different occupations within the bar/dance hall, all of them are generalized under this variable. The employees that are included are all people with occupations that require them to actively engage with the patrons. This includes alcohol vendors situated at the bar and all other employees that are able to assist any patron directly inside the establishment.

- Used in simulation: no

- Reasoning: It is assumed that the amount of active employees does not affect the patron behaviour as long as it exceeds a minimum amount, which is dependent on the amount of patrons. Above this limit, all customers can get assistance without having to wait (too long). Below this limit, patrons might become agitated as they might have to wait for long periods of time in order to get the assistance they require. It is assumed that the owner of the establishment always has enough active employees to exceed this threshold, as to not decrease the patron happiness. This variable can therefore be left out of the simulation.

Beverage stock

- Description: The amount of alcoholic beverages the establishment has in stock ready for sale. Complying with the research constraints, all types of beverages are generalised as one singular type. It is assumed that all patrons are allowed to buy these beverages and do to a certain extent enjoy consuming them. It is also assumed that all products are up to both legal and patron standards, making all of them sellable.

- Used in simulation: no

- Reasoning: It is assumed that the owner of the establishment has experience and can accurately determine the amount of beverages that are being consumed on an average day. This means that all patrons are able to buy whenever they want. For this reason, this variable does not affect the beverage income and is not included in the simulation.

Amount of seats

- Description: A bar or dance hall often has seats for patrons to sit on, but almost never enough bar-stools or chairs for everyone. When a patron is tired or does not want to stand, he or she can sit whenever a chair is still available.

- Used in simulation: no

- Reasoning: While patrons often try to sit down when they are tired, it does not replenish their energy significantly. Because the chair do not affect the energy level of the patrons, it does not affect the generated income. For this reason, this variable is not included in the simulation.

Food availability

- Description: Is it possible to buy food inside the establishment? Food can range from snacks to real meals, but is generalized as one undefined food item, assuming that all patrons are satisfied with this when requesting food. Food could generate more income besides beverages.

- Used in simulation: No

- Reasoning: Most bars or dance halls in the Netherlands do not sell food items. Food is ignored in the simulation in order to simulate an average bar or dance hall. Having food as a second source of income would also drastically complicate all variable relations, increasing the scope of the research. Keeping the scope of the research realistic is another reason for omitting food from the simulation.

Specified dance area

- Description: The establishment can have a specified dancing area. When such an area is available, patrons will not dance on anywhere else. The specific surface geometry or location within the establishment is ignored. The surface area size is given in cubic meters.

- Used in simulation: no

- Reasoning: There are no known differences in patron behaviour when a designated dance floor is available. It is therefore unnecessary to implement this variable in the simulation.

Patron specific variables

Money

- Description: All patrons can carry money, euros specifically. They can then only spend this money on alcoholic beverages. A patron can not spend more money than what they personally have: they can not lend money from other patrons. While real-life patrons sometimes pay for a group, this is not possible in the simulation, as it is assumed to not affect its results. Patrons have a random amount of money on them when entering the establishment, given to them using a [TODO] distribution [mean, var?].

- Used in simulation: yes

- Reasoning: It is essential for the patrons to have money, as it is necessary in order for them to buy alcoholic beverages, thus generating income.

Willingness to pay

- Description: How easy do the patrons part with their money in exchange for alcohol? Whenever a consumer has less money to spend, he/she is less likely to spend its remaining euros. The value of this variable thus decreases whenever the patron has less money, which might cause him/her to take more time before buying more drinks.

- Used in simulation: no

- Reasoning: While this might have an effect on the amount of money that the patrons will spend throughout the day, this effect would not be large. It is also not proven whether patrons actually decrease their spendings when they have less money. They will likely be under influence when this happens which might decrease their good judgement.

Has alcohol

- Description: Describes whether the patron currently has alcohol on his/her person. A patron will not buy any more alcohol whenever he/she already carries alcohol. When carrying alcohol, the patron might consume parts of it, which slowly intoxicates him/her. Whenever the alcohol is completely consumed, the patron has no alcohol anymore. The variable is defined as a percentage, with 100 percent denoting a full beverage, and 0 percent the absent of any drink.

- Used in simulation: yes

- Reasoning: In order to generate income for the establishment owner, it is important that the patrons can buy beverages. It would be unfair if they could buy drinks and not consume it afterwards. Furthermore, better mimics reality, as real life patrons generally consume their products as well.

Intoxication

- Description: A patron can become intoxicated when he/she consumes alcohol. This variable is represented as a percentage, with 0 percent representing a completely sober individual. When the patron consumes enough alcohol and reaches 100 percent, he/she will leave the establishment immediately. Intoxication changes the behaviour of a patron.

- Used in simulation: yes

- Reasoning: Intoxication alters the behaviour of the patron significantly. It also might cause a patron to leave early whenever they become too intoxicated. For these reasons, this variable is implemented in the simulation

Alcohol tolerance

- Description: This will show how much a certain patron can tolerate drinking alcohol. This is different per type of patron, some people can better stand drinking alcohol whilst not completely going drunk.

- Used in simulation: simplified

- Reasoning: This will not be used to its fullest in the simulation, it will probably be represented by a constant value which is the same for each patron.

group sizes

- Description: This will represent with how big of a group you are there. Since it will be more enjoyable to a patron, when the patron can converse and dance with more people he knows [9].

- Used in simulation: no

- Reasoning: At this moment it will not be included, however when the simulation would allow it this could be included as another variable.

Happiness

- Description: Happiness will depict how much a patron is enjoying himself. This can changes because of other variables in the simulation, for example when dancing and talking happiness will increase. This can be represented as a percentage in each patron, which will have certain threshold for leaving or staying.

- Used in simulation: yes

- Reasoning: With this it can be modeled how people are enjoying themselves. Which is an important part of the simulation. Since with this can be determined if people will stay when they are happy or go when they are unhappy.

Dance affinity

- Description: Dance affinity is here to show how much a certain patron enjoys to dance. Certain people will have a higher tendency to dance, whilst others will only dance in the right situations and circumstances.

- Used in simulation: simplified

- Reasoning: This variable will be relatively small and would prove to complex to model currently. Also since the variable is likely to change in the simulation for a patron, due to for example drinking alcohol and thus becoming more loose. This will however be represented by a the same constant value in each patron.

Energy

- Description: A Patron will have energy, with which they can do actions. When they do an actions, energy is subtracted from the energy of that patron. Possible action for example are dancing, standing, talking, drinking and buying. Which all have different energy costs. This will likely be used as a certain value from which patrons can differ from, with a small difference from the mean.

- Used in simulation: yes

- Reasoning: This variable is needed in the simulation, since people who are tired are likely to go from the bar.

Constraints

Constraints are limits that are set for the simulation. Constraints are needed in order to create a working simulation. Without these constraint a simulation would prove too complex to make, therefore these constraints have been made.

Bar

- Bar cannot be remodeled or renovated

- There is only one type of alcohol/drink

- Not taking into account other bars/competitors

- Given one night with certain amount of people inside

- Bar will not sell food

- No animals are allowed

- Drinks will not expire

- The bar only has one room in which people will dance and drink

People

- People will not start fights

- People will not complain

- People will not break stuff

- People will always pay and not steal

- People will go when they are unhappy or when they have no more energy

- People do not go to bathroom

Patron states

- Drinking: The only state that can be done simultaneously with any of the other states: In this state, the patron's alchohol will be drunk, increasing its intoxication level.

- Dancing: The patron is currently dancing and socialising with others. This actions does cost more energy than any other action.

- Talking: The patron is conversing with others, This does cost some energy.

- Buying: The patron is currently buying more alcohol for him/herself.

- Standing: In this state, the patron is inactive and unsocial. This state barely costs any energy.

Users

The main stakeholder for this simulation are bar/club owners. Since the simulation takes into account which factors a bar/club owners has any influence on, it can be a great tool for giving meaningful suggestions to generate more profit. Since it focuses mainly on how to maximize the sale of alcohol, it could also be useful in other contexts where selling alcohol is the main way of making profit, as long as the setting itself does not differ too much from the bar setting specified in the simulation. After all, differing from the defined setting could possibly introduce factors which change the result of the simulation. The simulation could even be useful in settings like student parties, where people want to get others as drunk as possible. Question is if it is ethical to use such a tool to get people drunk.

A secondary user for which this simulator might prove useful, are the people going to the bars and clubs. Assuming that customers spend more money when they enjoy themselves and leave when they are unhappy, using the results of the simulator to improve bars would mean that bars become more enjoyable. This is beneficial for the customers: they will have a better time.

State-of-the-art

AI and simulations

- Artificial Intelligence techniques: An introduction to their use for modelling environmental systems

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378475408000505

- Simulating exposure-related behaviors using agent-based models embedded with needs-based artificial intelligence (2018)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41370-018-0052-y/ Context: HUMANS exposure to a chemical. Because descriptions of where and how individuals spend their time are important for characterizing exposures to chemicals in consumer products and in indoor environments, and the existing method is difficult and labor-intensive, a simulation of longitudinal patterns in human behaviour was created. This is an agent-based model with a needs-based AI. Needs-based because humans make their decisions to take actions in order to fulfil needs. The paper describes how it is implemented. Meets critical need in field of exposure assessment. Only addresses a few needs, and not the complex ones.

- this paper presents the mechanism of Intelligent Adaptive Curiosity, an intrinsic motivation system which pushes a robot towards situations in which it maximizes its learning progress.

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/4141061

- This paper describes a novel system for creating virtual creatures that move and behave in simulated three-dimensional physical worlds. A genetic language is presented that uses nodes and connections as its primitive elements to represent directed graphs, which are used to describe both the morphology and the neural circuitry of these creatures.

http://www.karlsims.com/papers/siggraph94.pdf

- This paper explores selecting for evolvability in neural networks. Evolvability Search enables generating evolvability more easily and directly, facilitating its study and understanding, and may inspire future practical algorithms that increase evolvability without significant computational overhead.

http://www.evolvingai.org/mengistu-lehman-clune-2016-evolvability-search-directly

- In this paper digital organisms were used to investigate the ability of natural selection to adjust and optimize mutation rates.

http://www.evolvingai.org/clune-misevic-ofria-lenski-2008-natural-selection-fails

- This paper explores novelty search, a new type of Evolutionary Algorithm, has shown much promise in the last few years. A common criticism of Novelty Search is that it is effectively random or exhaustive search because it tries solutions in an unordered manner until a correct one is found. Its creators respond that over time Novelty Search accumulates information about the environment in the form of skills relevant to reaching uncharted territory, but to date no evidence for that hypothesis has been presented.

http://www.evolvingai.org/velez-clune-2014-novelty-search-creates-robots

- Evolutionary computing (2002)

https://www.cs.vu.nl/~gusz/papers/ec-intro-Eiben-Schoenauer.pdf This paper gives a general overview into evolutionary computing.

- Introduction to evolutionary computing (2003)

http://cslt.riit.tsinghua.edu.cn/mediawiki/images/e/e8/Introduction_to_Evolutionary_Computing.pdf This book gives an insight into how evolutionary computing works and how it can be implemented.

MABS

- Multi-agent Based Simulation: Where Are the Agents?

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/3-540-36483-8_1

- MABE (Modular Agent Based Evolver): A framework for digital evolution research (2017)

https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/isal_a_016 MABE is a modular and reconfigurable digital evolution research tool designed to minimize the time from hypotheses generation to hypotheses testing. MABE provides an accessible framework which seeks to increase collaborations and to facilitate reuse by implementing only features that are common to most experiments, while leaving experimentally dependent details up to the user. "One difficulty in Digital Evolution research stems from the need to develop the software used to conduct the re-search"

- Artificial Intelligence Techniques to Enhance Actors’ Decision Strategies in Socio-ecological Agent- Based Models (2016)

https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/iemssconference/2016/Stream-D/19/ Title is pretty self-explanatory. Provides an analysis of the types of AI learning algorithms employed in various application domains which use Agent-Based Models, their specific operationalization in an agent’s decision-making for various tasks, treatment of spatial and social environment in the design of AI learning algorithms, and the level of empirical information used in ABM. Also highlights the trends in the current practice of AI learning algorithms used to enhance ABMs.

- Agent-based model calibration using machine learning surrogates (2018)

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165188918301088 Tackles parameter space exploration and calibration of agent based models by combining machine-learning and intelligent iterative sampling. Results domanstrate that machine learning surrogates obtained using the proposed iterative learning procedure provide a quite accurate proxy of the true model and dramatically reduce the computation time necessary for large scale parameter space exploration and calibration.

- Representing the acquisition and use of energy by individuals in agent‐based models of animal populations (2012)

https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/2041-210x.12002# Exactly as the title suggests. Suggestion and evaluation of how to model animal energy needs in agent-based models.

- Using stylized agent-based models for population–environment research: a case study from the Galápagos Islands (2010)

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11111-010-0110-4 More about the utility of ABM's : here they are named useful for sharpening conceptualizations of population–environment systems, testing alternative scenarios, and uncovering critical data gaps. (Also about trade-offs between model complexity and abstraction.)

Specific animal population simulation

- A Generalized Computer Simulation Model for Fish Population Studies

https://afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1577/1548-8659(1969)98[505:AGCSMF]2.0.CO;2

- Application of Multi-agent Simulation in Animal Epidemic Emergency Management: Take an Example of AFS (Africa Fever Swine) Policy

http://www.dpi-proceedings.com/index.php/dtetr/article/view/31843

- VORTEX: a computer simulation model for population viability analysis

https://www.publish.csiro.au/WR/WR9930045

- An artificial intelligence modelling approach to simulating animal habitat interactions

- An overview of a simulation of an ecosystem housing predators and prey. The simulation has much hard coded behavior, allowing the simulation to get more realistic.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r_It_X7v-1E

Populations

- An overview of a simulation of an ecosystem housing creatures based on neural networks. With robust neural networks and no hard coded behaviours, this simulation allows for more emergent behaviour and potential realism at the cost of current realism.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=myJ7YOZGkv0

- An overview of a simulation of an ecosystem with a complex environment. This AI has hard coded features for interacting with the environment, however it can still evolve a neural network, striking a balance between the previous two simulations.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E-zcUzK8k7U

- A Study of AI Population Dynamics with Million-agent Reinforcement Learning (2018)

https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3237383.3238096

- Population based training of neural networks. Population based training discovers a schedule of hyperparameter settings rather than following the generally sub-optimal strategy of trying to find a single fixed set to use for the whole course of training.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.09846 (the paper)

https://deepmind.com/blog/article/population-based-training-neural-networks (a blogpost about the paper)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l-Ga0E9vldg (a talk about the paper)

- A talk by Jeff Clune (http://jeffclune.com/) about recent (2019) avancements in population-based search. Focusing on explicitly searching for behavioral diversity, open-ended search and indirect encoding.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g6HiuEnbwJE

- Exploring the Relationship between Experiences with Digital Evolution and Students' Scientific Understanding and Acceptance of Evolution (2018)

https://avida-ed.msu.edu/files/curricula/ABT_Exploring_Relationship__Understanding_Acceptance_Evo.pdf Uses a research-based platform for digital evolution in the classroom, found that engagement in lessons with Avida-ED both supported studentlearning of fundamental evolution concepts and was associated with an increase in student acceptance of evolution as evidence-based science. Also found a significant, positive association between increased understanding and acceptance. --> arguments for education as one of the users

- Effects of mass extinction on community stability and emergence of coordinated stasis with digital evolution (2018)

http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-NJNY201801012.htm Research based on digital evolution, can be used as application example.

Ecological risk assessment

- Next-generation ecological risk assessment: Predicting risk from molecular initiation to ecosystem service delivery

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412016300824 There have been exciting developments in in vitro testing and high-throughput systems that measure responses to chemicals at molecular and biochemical levels of organization, but the linkage between such responses and impacts of regulatory significance – whole organisms, populations, communities, and ecosystems – are not easily predictable. This article describes some recent developments that are directed at bridging this gap and providing more predictive models that can make robust links between what we typically measure in risk assessments and what we aim to protect.

- The role of agent-based models in wildlife ecology and management (2011)

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304380011000524 Wildlife-management ABMs disentangle habitat use and quality, and represent dynamic environments. Using adaptive movement ecology in changing landscapes permits scenario planning of future habitats. ABMs are excellent tools encompassing multiple disciplines and stakeholder interests. Can be used to substantiate arguments about why evolution simulations are useful in wildlife ecology and management.

Direct effects of alcohol on behaviour

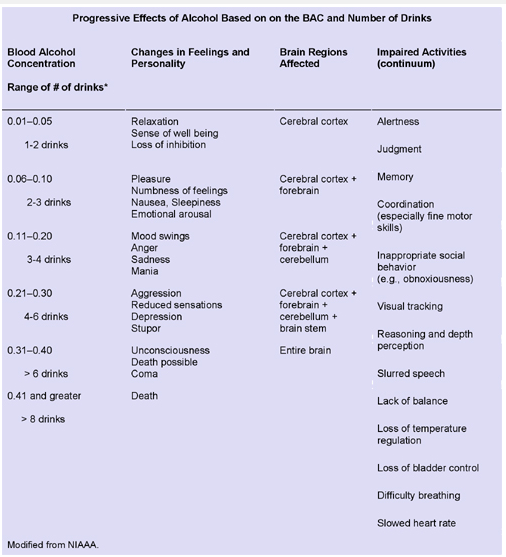

As is commonly known among many people, drinking alcohol makes one intoxicated, which can have all kinds of influences on people's behaviour [10].

The amount of alcohol it takes before one feels drunk, differs per person. It depends among other factors on sex, size, and ethnicity of the person [10]. A study into the number of drinks people needed before they considered themselves drunk found that African Americans reported to need less drinks before they felt drunk relative to whites. Hispanics reported to need more drinks than whites. These effects were stronger in the under 30 group. [11] [NICE FIGURES IN PAPER]

The same study found that on average, woman reported to need 4.15 drinks to feel drunk. Men needed 6.63 on average [11].

It has also been found that BAC estimates the degree of intoxication [10]

- Alcohol produces an effect that may be described as disinhibitory related to an increase in behaviours that otherwise normally occur at a low rate. Many of these behaviours may be forms of risk-taking that result in aversive consequences to self or others.

- Choices for the response option defined as risky were systematically increased as a function of alcohol dose.

Alcohol and impulsivity

Multiple studies have been done on how alcohol intoxication influences impulsivity. This is often done by investigating degree of discounting, as degree of discounting correlates with tests on impulsivity [17]. While one study found that alcohol had no effect on delay or probability discounting [17], another found that alcohol reduced impulsivity in that no-alcohol participants discounted delayed rewards at higher rates than intoxicated participants [18]. An explanation for this contradiction could be that the first study completed the delay-discounting task five times, which possibly established a stable pattern of responding across the alcohol and placebo sessions, where the second study did not do that. In any case, it is clear that under certain conditions, alcohol intoxication reduces impulsivity. It was also found that intoxicated participants were more likely to show lack of fit to the hyperbolic model, suggesting they respond less consistently.[18]

Motivations for drinking

- Primary motivations for drinking include making it easier to socialize, loosen up, or open up [9].

- Becoming drunk could also be a way for young people to cope with the stresses and boredom of everyday life[9].

- Desires to drink and become intoxicated can also be framed around pleasure or fun[9].

Social influences on alcohol intake

SOCIAL GROUPS EN WANNEER ZE GAAN DANSEN DUS MINDER ALCOHOL DRINKEN?

In-Pub behavioural data

- People who were in their local pub or community pubs were in significantly smaller social groups than those who were casual visitors in city centre bars. Those attending their local and those in community pubs were in conversation sized groups (maximum size 4): [19]; [20][21] [22] [23], whereas casual customers and those in city centre bars were typically in parties that were larger than the normative limit for conversations.

- The size of a social group had significant consequences for its dynamics. Conversations became more fragmented as the size of the group increased. And more people dropping out of the conversation as group size increased. The proportion of people who were not engaged with a conversation they were physically part of was significantly higher in city centre bars than in community pubs.

Social groups and their influence on the drinking behaviour of people in a bar

Drinking and becoming drunk is a highly sociable activity [9]. Therefore one can imagine that the composition of ones drinking group can have quite an influence on how you drink. Several studies support that indeed, the social context of a drinking occasion can impact drinking behaviour [25] [26]. Several studies shed light on more specific social factors and their corresponding impacts.

For starters, a larger drinking-group size is associated with heavier drinking [27] [28] [5]. This seems quite logical: with more people, there are more people doing rounds, thus there is a longer time between having to get alcohol yourself while still getting a continuous supply of alcohol. It has previously been found that when purchasing drinks in rounds, especially males tend to consume more alcohol [5][29].

The relationship between the number of friends and the number of drinks was stronger for men than for women [28], which corrolates with men drinking more when drinks are purchased in rounds. Also, men were found to consume more alcohol than women, particularly at the beginnings of the evening. [28].

On top of the number of friends you take with you, the gender composition of those friends also influences drinking behaviour. A study found that both males and females consume significantly more drinks in mixed-gender groups. [30] [5]. There is a difference between males and females here: men consumed more drinks in groups with an equal amount of males and females and groups with men in the majority. They also consumed more drinks with in a group with men only compared to woman only.

Woman however, although they did consume more drinks in mixed-gender groups, consumed significantly fewer drinks in groups with men only than groups with woman only. [30]

There are more differences between male and female pub-goers. One study found that male friends or acquaintances were the main sources of pressure on people to drink or drink more [31]. According to the same paper, pressure to drink also depends on religion and gender. Another study found that indirect pressures to drink play a more significant role than direct pressures [32].

Peer pressure

Drinkers with companions who consumed large amounts of alcohol tended to consume more alcohol and tended to have higher drinking rates [29] [33].

Conclusions

- Larger drinking group size => more alcohol. Stronger relationship for men than for women.

- Men consume more alcohol than women, particularly at the beginning of the evening

- Both men and women like mixed-gender groups the most to drink in. People hate drinking with only men.

- Men are the main source of pressure to drink more

- Peer pressure is a thing in alcohol drinking

Music and its influence on the behaviour of people in a bar

Music can have quite an influence on how people behave in social settings. Most people like background music: studies have found that people spend less time drinking in bars that don’t play music [34]. It goes even further: according to a previous study, loud music makes people drink 31% more [3] [4] [5]. The reason behind this is could be that when people can not communicate due to the noise in the bar, they start focussing on drinking [35]. Another explanation is that high sound levels may cause higher arousal, which leads the subjects to drink faster and order more drinks [3] [6].

Another study links faster music to faster drinking [36] [37]. However, a different study links slower music to more sales. Customers stayed about the same amount of time but spent more during slow music than during normal or fast music. [38]. An explanation for this difference is that people prefer to listen to music that moderates their state of arousal [39]. During a relaxing activity like an afternoon beer, people prefer slow low-arousal music, while during a night out people prefer music that further heightens their state of arousal. On top of that, studies found that the genre of music matters. Jacob (2006) found that when playing drinking songs in a bar, the duration of stay and spending both are increased [7]. Further research supported this and claimed that customers exposed to textual references to alcohol spent significantly more on alcoholic drinks than those who were not [8].

It was also found that in social context, people modify their bodily behaviour according to the dynamic level of the bass drum. More specifically, they move more actively and display a higher degree of tempo entrainment as the sound pressure level of the bass drum increase [40]. This could be interesting if a correlation between dancing and alcohol could be found.

Conclusions

- Background music is a plus

- Louder music => more drinks

- Faster music => faster drinking, but not during a relaxing after noon beer, then slower music => more beer

- Drinking songs => more drinks

- more bass => more dancing

- Day of the week: heavy drinking occurs mostly on Saturday evenings followed by Friday evenings. This is because young people do not have any responsibilities the next day [41]

Scent

Apart from the earlier named direct influences on alcohol intake, a lot of other factors can influence how people behave on a night out.

One of these factors is scent: on a night out, one may encounter many scents, both pleasant and vile. Sweating bodies, alcohol, you name it. It would seem logical that ambient scents that mask the vile odours could contribute positively to the night-time experience. A previous study confirms this: they tested the scents of orange, seawater and peppermint, and found that all scents enhanced dancing activity and improved the evaluation of the evening, music and mood [42]. Additionally, they found that the increase in dancing coincided with an increase in temperature in the club. This may lead to the customers wanting more alcohol: if it is hot, what’s better than a cold beer to cool off?

Factors that influence how much people like a bar

Apart from knowing how to influence the alcohol intake of customers, it is important to know how to get customers. There have been a few studies that worked with focus groups in order to find out what people wanted from bars.

First of all we have security. Most bars have security, if only to dismiss all people below legal drinking age. The nature of the security presence outside a bar can be a good indicator of the level of security inside a bar. Studies found that a more formal attire offers a greater image of security [43] [44]. This is because people do not like going somewhere where you do not feel safe. People however wanted the security personal to look friendly as well, they did not want to feel threatened by the very security that should protect them [44]. There is a difference here between male and female clientele: while most men belief that more formal attire offers the greatest image of security, only about 50% of woman have the same belief, while the other 50% prefer an informal attire.[45]

The clientele is important as well. People prefer a mix of male and female clientele, with the majority liking a male-dominated place the least [43]. This seems to corollate with the fact that people drink more in mixed-gender groups. Women like a mixed clientele more than men; men like a predominantly female clientele about as much as a mixed clientele [45]. Males offered an explanation for their preference for mixed-gender bars: they identified woman as critical factor in the decision to select a bar [44] [45]. How busy it looked is also named as a critical factor in the decision to select a bar. It should not be too busy, but not to quiet either [45].

Then we have the seating. Opposing the stereotypical image of pub customers on barstools, the same study found that sofas are the most preferred as seating arrangement inside a venue. Seating and bar stools proved far less popular. People like relaxing and taking a break from the pushing and shoving every now and then [43]. Woman like individual seating particularly well, but still less than sofas [45].

The type of venue was found to be important as well. Both men and women prefer a traditional bar, but men prefer this more than women. Women have as close second the wine bar. A Latin themed bar is least liked by both men and women [45] [44].

Lastly, the alcohol prices are important for choosing a bar, but not as much as other factors. People like everyday low alcohol prices but are prepared to pay a bit more, as long as it is not too much [43]. Low alcohol prices do have a significant effect on alcohol intake however: another study found that a happy hour with price reduction increases alcohol consumption. When the purchase price was reduced by half, casual and heavy drinkers increased their consumption eight and nine times respecively [46].

Conclusions

- A nice scent in the pub ==> better evening

- Security: For male formal, for female does not matter

- Mix of male and female clientele

- Not too quiet, not too busy

- Sofas > individual seating > bar stools

- Low alcohol prices => more alcohol intake

Activities and alcohol consumption

Available activities in bars, like playing games, watching TV or making conversation, has influence on the alcohol intake of people as well. A study found that especially in males, active pastime activities like playing pinball, playing cards or playing table football, result in slower drinking than passive pastime activities like being alone, making conversation or watching TV [5][2]. The males in the study displayed the same drinking rate as women when active, but a slower one when passive. However they compensate for this 'lost time' during the passive activity following the active one by drinking more. They also do drink more alcohol during conversation than females [2].

Conclusions

- Passive activities = more alcohol intake than active activities

- After active activities, males compensate for their "lost time" by drinking slightly faster.

Other

Efkes buiten deze pagina houden

- Craving and Attentional Bias Respond Differently to Alcohol Priming: A Field Study in the Pub

https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/253859

- Pastime in a pub: Observations of young adults' activities and alcohol consumption

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306460306001638

- Visiting Public Drinking Places: An Explorative Study into the Functions of Pub-Going for Late Adolescents

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/10826089909039408

- Reporting on responsible drinking: a study of the major UK pub‐owning companies

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2006.00469.x

- Young people and alcohol: influences on how they drink

http://www.ias.org.uk/uploads/pdf/Young%20people/alcohol-young-adults-summary.pdf

- Why Do You Dance? Development of the Dance Motivation Inventory (DMI)

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0122866

- Spatiotemporal variations in nightlife consumption: A comparison of students in two Dutch cities

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0143622814001647 Important between and within city differences exist in nightlife consumption. Typologies of city-centre nightlife consumption patterns are created. Participation in different patterns is most strongly shaped by level of education. Contrary to popular discourses not all patterns involve excessive alcohol consumption. Alcohol consumption needs to be seen as part of the social practice of going out.

- ‘That right level of intoxication’: A Grounded Theory study on young adults’ drinking in nightlife settings (2014):

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13676261.2015.1059931 The present study examined the meaning and functions of drinking across different nightlife settings (e.g., bars, dance clubs) in a sample of Italian young adults. Results indicated that three major categories of social nightlife settings associated with different meanings and uses of alcohol: a more moderate social drinking in bars, a pursuit of a desired level of intoxication in dancing settings, like nightclubs, with festivities and celebratory settings most associated with alcohol abuse and heavy drunkenness as a mean to maximize the celebration and the uniqueness of the event.

- Measuring College Students' Alcohol Consumption in Natural Drinking Environments: Field Methodologies for Bars and Parties (2007):

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0193841X07303582 This article presents field methodologies for measuring college students' alcohol consumption in natural drinking environments. Specifically, we present the methodology from a large field study of student drinking environments along with some illustrative data from the same study.

- Blood alcohol concentrations among bar patrons: A multi-level study of drinking behaviour (2008):

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0376871609000325 The study examines: (1) drinking behavior and settings prior to going to a bar; (2) characteristics of the bar where respondents are drinking; (3) person and environmental predictors of BrAC (blood alcohol concentration) change (entrance to exit).

- Cognitive Performance Measured on the Ascending and Descending Limb of the Blood Alcohol Curve

https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2FBF00401185.pdf

- THE EFFECT OF ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION ON RISK-TAKING WHILE DRIVING

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0306460387900347

Approach

1.Determine important variable for simulation

2. Research state of the art.

- 2.1 Determine correlations between the determined variables and alcohol consumption trough state of the art.

- 2.2 formalyze hypothesis etc.

3.Determine unknowns in correlations, research those correlations.

- 3.1 Set up a research plan.

- 3.2 Execute the research plan.

- 3.3 Analyze the results.

4. Set up a simulation using the found correlations.

- 4.1 Create a minimum viable product: a bar setting with AI using that bar.

- 4.2 start implementen each of the correlations found in 2 and 3.

5 Analyze the simulation

- 5.1 Change variables, optimize the simulation.

- 5.2 Refer back to research and hypothesis, is our simulation realistic and how does it comply with our hypothesis?

- 5.3 If neccecary review steps 2, 3 and 4.

6 Finalize wiki and conclusions

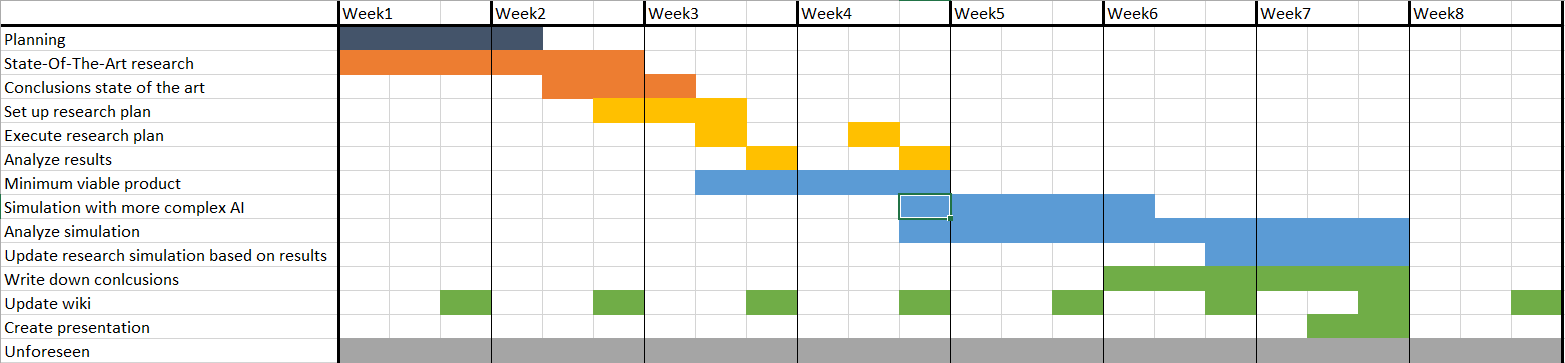

Planning

- Week 1: research state-of-the-art, finalise plan

- Week 2: More research, state requirements for simulation, create research plan for filling in the blanks of the state-of-the-art.

- Week 3: Implemented first version of simulation with only basic features

- Week 4: Implemented second version simulation with requirements implemented

- Week 5: Performing simulation, documenting results

- Week 6: Performing simulation, documenting results

- Week 7: Compare results to real life, create conclusion

- Week 8: Finalise wiki

Milestones

| Tasks | Estimated Time |

|---|---|

| Planning | 12:00 |

| State-Of-The-Art research | 75:00 |

| Conclusions state of the art | 5:00 |

| Set up research plan | 5:00 |

| Execute research plan | 50:00 |

| Analyze results | 20:00 |

| Minimum viable product | 50:00 |

| Simulation with more complex AI | 100:00 |

| Analyze simulation | 75:00 |

| Update research simulation based on results | 50:00 |

| Write down conlcusions | 20:00 |

| Finalize wiki | 20:00 |

| Create presentation | 10:00 |

| Unforseen | 100:00 |

| Total | 592:00 |

Deliverables

State-of-the-art

A list of variables influencing behaviour at a bar setting.

A list of missing variables influencing behaviour at a bar setting.

A hypothesis on how the results our simulation would create.

A research plan detailing how to fill in the blanks of the state of the art.

Results of our research.

A minimum viable product: a simulation that can houses AI that can navigate a bar setting.

Extension of the minimum viable product trough implementing more complex behaviours found in the research.

Results out of the simulation, a set of factors and the behaviour it creates in the simulation.

Finalized wiki and conclusions.

A presentation

Who is doing what

Week 1

| Name | Total | Break-down |

|---|---|---|

| Daan | 2h | Discussing the subject |

| Job | 2h | Discussing the subject |

| Sanne | 5h | Making a draft for the wiki (0.5 h), Gathering links for the State of the Art (2.5h), Discussing the subject (2h) |

| Jasper | 3h | Gathering articles for state-of-the-art (1.5 h), Discussing the subject (2h) |

| Wietske | 6h | Working on the wiki (0.5 h), Gathering articles for state-of-the-art (3.5 h), Discussing the subject (2h) |

Week 2

| Name | Total | Break-down |

|---|---|---|

| Daan | 10h | Working on the wiki (3 h), gathering articles for state-of-the-art (3 h), Discussing the subject (4h) |

| Job | 10h | Working on the wiki (2 h), gathering articles for state-of-the-art (4 h), Discussing the subject (4h) |

| Sanne | 10h | Working on the approach and planning (3h), working on the state of the art (3h) Discussing the subject (4h) |

| Jasper | 10h | Working on the wiki (2 h), gathering articles for state-of-the-art (4h) Discussing the subject (4h) |

| Wietske | 11.5 h | Working on the wiki (1 h), discussing the subject (4h), gathering articles for state-of-the-art (3 h), organizing sources on wiki by subject (1h), writing about the effect of music (1h), writing about social groups and alcohol(1.5 h) |

Week 3

| Name | Total | Break-down |

|---|---|---|

| Daan | 11h | Working on the wiki (7h), gathering articles for state-of-the-art (), Discussing the subject (4h) |

| Job | 12h | Working on the wiki (6h), gathering articles for state-of-the-art (2h), Discussing the subject (4h) |

| Sanne | 4h | Working on the approach and planning (), working on the state of the art () Discussing the subject (4h) |

| Jasper | 11h | Working on the wiki (1h), Discussing the subject (4h), setup Github(0.5h), Started programming simulation (5.5h) |

| Wietske | 18h | Working on the wiki (2 h), discussing the subject (4h), gathering articles for state-of-the-art (1 h), writing about factors in a bar (2 h), incorporating articles in state-of-the-art (2h), reading articles (4h), writing about alcohol (3h) |

References

- ↑ Mintel, 2002. Nightclubs. UK, Leisure Intelligence Pursuits, December 2002.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Sander M. Bot, Rutger C.M.E. Engels, Ronald A. Knibbe, Wim H.J. Meeus (2007). Pastime in a pub: Observations of young adults' activities and alcohol consumption. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.05.015

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Guéguen, N., Jacob, C., Le Guellec, H., Morineau, T., & Lourel, M. (2008). Sound level of environmental music and drinking behavior: A field experiment with beer drinkers. Alcoholism:Clinical andExperimentalResearch,32 (10), 1795-1798.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. "Loud Music Can Make You Drink More, In Less Time, In A Bar." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 21 July 2008. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/07/080718180723.htm>.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 R. A. Knibbe, I. Van De Goor & M. J. Drop (1993) Contextual Influences on Young People's Drinking Rates in Public Drinking Places: An Observational Study, Addiction Research, 1:3, 269-278, DOI: 10.3109/16066359309005540

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Sound Level of Background Music and Alcohol Consumption: An Empirical Evaluation August 1, 2004 https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.99.1.34-38

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Jacob, C. (2006). Styles of background music and consumption in a bar: An empirical evaluation. International Journal of Hospitality Management,25 (4), 716–720.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rutger C. M. E. Engels, Gert Slettenhaar, Tom ter Bogt, Ron H. J. Scholte (2011). Effect of Alcohol References in Music on Alcohol Consumption in Public Drinking Places. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00182.x

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Geoffrey Hunt, Molly Moloney & Adam Fazio (2014) “A Cool Little Buzz”: Alcohol Intoxication in the Dance Club Scene, Substance Use & Misuse, 49:8, 968-981, DOI: 10.3109/10826084.2013.852582

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 The Alcohol Pharmacology Education Partnership https://sites.duke.edu/apep/module-2-the-abcs-of-intoxication/content-the-blood-alcohol-concentration-bac-estimates-the-degree-of-intoxication/ retrieved on 01-03-2020

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 William C. Kerr, Thomas K. Greenfield, Lorraine T. Midanik (2006) How many drinks does it take you to feel drunk? Trends and predictors for subjective drunkenness. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01533.x

- ↑ Vogel-Sprott M (1967) Alcohol effects on human behavior under reward and punishment. Psychopharmacologia 11:337–344

- ↑ Glowa JR, Barrett JE (1976) Effects of alcohol on punished and unpunished responding of squirrel monkeys. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 4:169–173

- ↑ Vogel RA, Frye GD, Wilson JH, Kuhn CM, Kuepke KM, Mailman RB, Mueller RA, Breese GR (1980) Attentuation of the effects of punishment by ethanol: comparisons with chlordiazepoxide. Psychopharmacology 71:123–129

- ↑ Josephs RA, Steele CM (1990) The two faces of alcohol myopia: attentional mediation of psychological stress. J Abnorm Psychol 99:115–126

- ↑ Lane, S.D., Cherek, D.R., Pietras, C.J. et al. Alcohol effects on human risk taking. Psychopharmacology 172, 68–77 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-003-1628-2

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Richards, Jerry B and Zhang, Lan and Mitchell, Suzanne H and Wit, Harriet (1999) DELAY OR PROBABILITY DISCOUNTING IN A MODEL OF IMPULSIVE BEHAVIOR: EFFECT OF ALCOHOL, Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 2:71, 121—143, DOI: 10.1901/jeab.1999.71-121

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Catherine N. M. Ortner, Tara K. MacDonald, Mary C. Olmstead, ALCOHOL INTOXICATION REDUCES IMPULSIVITY IN THE DELAY-DISCOUNTING PARADIGM, Alcohol and Alcoholism, Volume 38, Issue 2, March 2003, Pages 151–156, https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agg041

- ↑ Dunbar, R., Duncan, N., & Nettle, D. (1995). Size and structure of freely forming conversational groups. Human Nature, 6, 67–78.

- ↑ Dezecache, G., & Dunbar, R. (2012). Sharing the joke: the size of natural laughter groups. Evolution & Human Behavior, 33, 775–779.

- ↑ Dunbar, R. I. M. (2016). Sexual segregation in human conversations. Behaviour, 153, 1–14.

- ↑ Krems, J. A., Dunbar, R. I. M., & Neuberg, S. L. (2016). Something to talk about: are conversation sizes constrained by mental modeling abilities? Evolution and Human Behavior, 37, 423–428.

- ↑ Dahmardeh, M. & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2017). What shall we talk about in Farsi? Content of everyday conversations in Iran. Evolution and Human Behavior, in press.

- ↑ Dunbar, R.I.M., Launay, J., Wlodarski, R. et al. Functional Benefits of (Modest) Alcohol Consumption. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 3, 118–133 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-016-0058-4

- ↑ Monk R. L., Heim D. (2014). A systematic review of the alcohol norms literature: a focus on context. Drugs Educ Prev Policy 2014; 21: 263–282. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/09687637.2014.899990

- ↑ Senchak, M., Leonard, K. E., & Greene, B. W. (1998). Alcohol use among college students as a function of their typical social drinking context. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 12(1), 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.12.1.62

- ↑ Kairouz S., Gliksman L., Demers A., Adlaf E. M (2002). For all these reasons, I do... drink: a multilevel analysis of contextual reasons for drinking among Canadian undergraduates. J Stud Alcohol 2002; 63: 600–608. https://www.jsad.com/doi/abs/10.15288/jsa.2002.63.600

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Thrul J., Kuntsche E. (2015). The impact of friends on young adults’ drinking over the course of the evening—an event‐level analysis. Addiction 2015; 110: 619–626.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 P. P. AITKEN, AN OBSERVATIONAL STUDY OF YOUNG ADULTS' DRINKING GROUPS—II. DRINK PURCHASING PROCEDURES, GROUP PRESSURES AND ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION BY COMPANIONS AS PREDICTORS OF ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION, Alcohol and Alcoholism, Volume 20, Issue 4, 1985, Pages 445–457, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a044569

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Johannes Thrul, Florian Labhart, Emmanuel Kuntsche (2016). Drinking with mixed‐gender groups is associated with heavy weekend drinking among young adults (2016): https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/add.13633

- ↑ Akanidomo K. J. Ibanga, Victor A. O. Adetula, Zubairu K. Dagona (2009). Social Pressures to Drink or Drink a Little More: The Nigerian Experience. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/009145090903600107

- ↑ Pia Mäkelä, Antti Maunu (2016). Come on, have a drink: The prevalence and cultural logic of social pressure to drink more. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2016.1179718

- ↑ The modeling of alcohol consumption: a meta-analytic review. B M Quigley and R L Collins Journal of Studies on Alcohol 1999 60:1, 90-98

- ↑ Loud Music Is Scientifically Proven to Make You Drink More https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2017/11/14/loud-music-drinking/

- ↑ Why Loud Music in Bars Increases Alcohol Consumption https://www.spring.org.uk/2008/09/why-loud-music-in-bars-increases.php

- ↑ McElrea, H., & Standing, L. (1992). Fast music causes fast drinking. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 75 (2), 362.

- ↑ Milliman, R. E. (1986). The influence of background music on the behaviour of restaurant patrons. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(2), 286-9

- ↑ Samuel Joseph Down (2009). The effect of tempo of background music on duration of stay and spending in a bar. https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/20304/URN_NBN_fi_jyu-200905271640.pdf?sequence=1

- ↑ Hargreaves, D. J., & North, A. C. (Eds.). (1997). The social psychology of music. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ The Impact of the Bass Drum on Human Dance Movement. Edith Van Dyck, Dirk Moelants, Michiel Demey, Alexander Deweppe, Pieter Coussement, Marc Leman. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol. 30 No. 4, December 2012; (pp. 349-359) DOI: 10.1525/mp.2013.30.4.349

- ↑ Kuntsche E., Gmel G. 2013. Alcohol consumption in late adolescence and early adulthood - where is the problem? https://serval.unil.ch/notice/serval:BIB_93F9E1EBAF0B

- ↑ Schifferstein, H.N.J., Talke, K.S.S. & Oudshoorn, D. Can Ambient Scent Enhance the Nightlife Experience?. Chem. Percept. 4, 55 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12078-011-9088-2

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Krzysztof Kubacki, Heather Skinner, Scott Parfitt, Gloria Moss (2007). Comparing nightclub customers’ preferences in existing and emerging markets. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2006.12.002

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 Heather Skinner, Gloria Moss and Scott Parfitt (2005). Nightclubs and bars: what do customers really want? The Business School, University of Glamorgan, Pontypridd, UK

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 45.5 Gloria A. Moss, Scott Parfitt, Heather Skinner (2009). Men and Woman: Do They Value the Same Things in Mainstream Nightclubs and Bars? https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1057/thr.2008.37

- ↑ Babor, T.F., Mendelson, J.H., Greenberg, I. et al. Experimental analysis of the ‘happy hour’: Effects of purchase price on alcohol consumption. Psychopharmacology 58, 35–41 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00426787